- Home

- Jack Hamlyn

Necrophobia - 01 Page 10

Necrophobia - 01 Read online

Page 10

“I think they’re kids,” Diane said.

We split up and began touring amongst the various implements, both with our Sigs in our hands because we honestly did not know what to expect. I came around the side of an immense tiller and somebody ran off. It was a kid. A girl. She charged off back towards the parts department.

“Hey!” I said. “I won’t hurt you!”

I saw Diane on a merry chase trying to catch a little boy who was agile as a monkey. Here, then gone. Ducking and darting through the implements, he left Diane in his dust. She circled around a display of garden tractors and the boy jumped over a few mowers, darted to the left and I grabbed him, holstering my gun. He was wild and dirty, frothing at the mouth and screeching at me.

“I WON’T HURT YOU!” I shouted in his face, shaking him.

He calmed down and just stood there, staring at me with wide eyes.

Then another voice said, “LEAVE MY BROTHER ALONE!”

The little girl came charging at me with a hammer held high and Diane stuck out her leg and tripped the kid. She hit the floor and started balling and I let the boy go to her. They held each other and stared at us, looking more like animals than children.

“We’re normal,” I told them. “You don’t have to be afraid of us.”

They looked unconvinced.

“Do you have anywhere to go?” I asked them.

They still stared.

“We have a safe place with food.”

They continued staring.

“It’s hopeless, man,” Diane told me.

I figured she was right. Those kids were seeing us as a visible threat so we walked off towards the front of the showroom where we could watch the parking lot. And once we got there, we got an unpleasant surprise because there were eight or ten zombies coming through the lot. Most, I noticed, had been elderly when they died. It wasn’t surprising, I suppose, since more elderly died daily than of any other age group. And they would be the ones that would probably die from the virus first: like any other predator, our mystery organism, Necrophage, would target the sick and the weak first.

“Shit,” I said.

“They were following us,” a voice said.

The boy and girl were standing not ten feet away. They were brother and sister, both with the same angular faces, shiny black hair, and huge dark eyes. And both dirty like they’d been sleeping under sheds and in ditches.

“They’re not fast,” the boy said. “They’re slow. But they keep coming and coming. You can run away…but sooner or later you have to sleep. They don’t.”

The girl was still just watching us. She hadn’t quite made up her mind.

“You can come with us where it’s safe,” I told him.

And he said: “It got our building. It got everyone.”

As Diane watched the inexorable approach of the zombie corps, the boy told me his name was Davis and his little sister was Maria. He was nine-years old and she was seven. The infection hit their building five days before. It started in the morning and by afternoon it had spread everywhere. People were stumbling around in the hallways, delirious and screaming, some were convulsing. The man from next door was crawling around on his hands and knees and he was drenched with his own urine and vomit, soiled with his own feces. Davis and Maria stayed locked in their apartment while their mother got sicker and sicker. She was sweating and shaking, her eyes rolling back in her head. In a final moment of lucidity she told them to get out of Yonkers, to go to their Uncle Martin’s farm (he had apple orchards). By late in the afternoon, she started screaming and thrashing and then she died. They packed up what they could in their school backpacks and not even an hour later their mother “woke up” (his words) and came after them. They ran away and barely got out of the building because there were zombies everywhere.

Even in the streets.

Diane said, “They’re getting closer.”

Tuck came back wheeling a cart with five big black batteries on it. “Where’d you find these scrubs?” he said.

“We got company,” Diane told him.

Tuck saw. “Shit. We gotta fly.”

I motioned to Davis and Maria. “I told them they could come with us.”

Tuck just looked at me.

“Unless you want to leave them for the zombies,” I said.

Maria ran right to him and wrapped herself around his legs. Tuck looked uncomfortable. “Hey,” he said. “Hey.”

“Please,” Maria said. “Please take us away.”

She had a sweet little voice that had probably melted many a heart in its time and Tuck just scowled. “Yeah. All right. Come on. Just do what you’re told.”

We started out of the building and Tuck raced over to the Jeep.

The dead were mere feet from it and he dropped three of them, smashed another in the face to drive it back, and got behind the wheel. He backed across the parking lot and I got the kids in the backseat and we loaded the batteries. Then we jumped in the front and Tuck stomped the accelerator. The zombies he had dropped were being fed on by most of the pack, but three others were coming for the Jeep. He floored it and smashed them out of the way. The Jeep with its reinforced bumper scattered them like nine pins. One of them thumped up over the hood and slid over the roof before falling away.

Out on the road, there were dozens of zombies in the fields, just walking and walking.

“Hey,” Diane said when she spotted that Maria was terrified and close to tears. She dug in her plastic bag. “Who wants a peanut butter cup?”

She got two takers right away.

PANIC LIST

We’ve got a couple new faces: Maria and Davis, brother and sister.

Glad to have them, but they’re kids. That gives me something else to worry about, I suppose.

I kind of wish they were adults, people who could fight with us.

We’re in pretty good shape at the tower, thanks to Tuck.

Diane and Ricki have been kinda/sorta getting along

Dick remains a problem. I wish there was a way to snap him out of it before he does damage to himself or the rest of us.

Still seeing a few choppers from time to time.

New reports are conflicting. What’s really going on?

Thus far, we have power and water. But for how long?

BACK AT THE FARM

Ricki and Diane took our guests out to the pond where we did most of our bathing and cleaned them up. When they got back they looked pretty much like kids and not much like animals at all. Still, though, in their eyes there was something that did not belong: fear, cold fear. Their eyes darted very quickly in their sockets, always on the move. Both of them reminded me of squirrels with their quick jerky movements. They continually cocked their heads, listening. They were prey animals and they acted like prey animals. It would take time to turn them back into children.

Paul was ecstatic, of course, to finally have some kids around. I thought it would be good for him to spend a little less time with Tuck and more with some kids his age. The way he was going it wouldn’t be long before he became a foul-mouthed, hard-assed, blood-spitting Marine just like Tuck. Neither Ricki nor I cared for the idea of that.

Jimmy was good with the kids, of course, instantly reverting into his grandfatherly demeanor when he saw them. He showed them card tricks and played Snakes-and-Ladders with them on a board he’d made himself. They were good kids: both kind and very polite, raised-up right. Ricki took an instant shine to them. Tuck, however, just glared at them when they got too close to him, but Maria was fascinated by the gruff old Recon Marine. She was always following him around and asking where he was when he was gone and offering him food from her plate. She drew pictures of him and told him he was the toughest man in the world and told everyone that he would protect us like her daddy had protected them before he was killed by an Army patrol in the streets.

That did it.

Tuck melted.

He went from a bristling, hard-edged, jar-headed Marine to a soft,

shapeless blob of warm butter. Maria wrapped him around her little finger and he was powerless. It wasn’t long before her drawings were taped all over his board in the panic room (as I called it) and she was sitting on his lap and riding atop his shoulders. He played songs for her on his fiddle and told her stories I knew he made up on the spot. I don’t want to sound too soppy, but it was pretty damn touching.

Things were going well.

Except for the world outside the fence.

Just like Tuck predicted, the dead were building up out there and at last count there were over fifty of them. That’s when Tuck pulled me and Jimmy aside and said, “It’s time to thin the herds.”

My idea was to go out on the walkway and do a little sniping, but that wasn’t practical because of the fence. Since the deadheads were clustering up quite near to it now, we’d have to shoot through the fence to hit them and that meant hitting the fence and we saw no reason in weakening the integrity of our barrier. Out also was Jimmy’s idea of killing the juice on the fence and walking right up there and shooting through it. Tuck figured that was just asking for trouble—if we got close to it, they’d rush us and no sense risking an inhuman wave attack if we could possibly avoid it.

“Defense is great,” Tuck said. “If we could hole up in here for the next couple years and never have to leave, it’d be great. But we can’t do that. And we can’t have the herds piling up outside the fence. That means we have to get out there and carry the fight to them.”

“Sounds risky,” Jimmy told him.

“It is. But we don’t have a choice.”

“What do you got in mind?” I told him.

“An ambush.”

It was an interesting idea, but I wasn’t convinced it was a good one. The ambush is a great military tactic to thin the numbers of the enemy. When they work—which is often—they can be devastating to enemy combatants. But when they fail, they can be just as devastating to your own people. I wasn’t sure that using traditional soldiering techniques against a very non-traditional enemy was the best idea. And being out there, mixing it up with the walking dead wasn’t something I much cared for.

“When I was in ‘Nam and we’re talking 1969/1970 here, my first tour over there,” Tuck told us, “we had rules of engagement that stifled us and supported the assholes we were there to fight. The VC and NVA units would slip across the border from Cambodia and Laos, hit our units, then creep back across again. We weren’t allowed to follow. Rules of engagement. The U.S. wasn’t at war with Cambodia or Laos so we couldn’t enter their territory. The North Viets weren’t at war with them either, but they had no rules of engagement: they’d hit Army and Marine units then run over the border before they got their asses kicked. That’s when battalion brought us in, Force Recon. Our job was to locate these border crossings, reconnoiter them, and when the Viets were safely within Vietnam again, call down precise air strikes and artillery bombardments on them. We did a lot of that. The Viets changed their infiltration routes a dozen times and we had to scout them out again and again.

“But reconnaissance was only one of our duties. Battalion wanted us to engage in serious H & I, Harassment and Interdiction. Which, for us, meant ambushes and sniping, mining their trails and setting out booby traps along their evasion routes. We got very good at it. We killed them in fucking numbers. I remember one particularly sweet ambush. A reinforced NVA/VC company was slipping across the border from Laos using a carefully-concealed high speed trail in the Que Son Mountains. They’d infiltrate to Da Nang, hit us, and retreat back into Laos. We watched them, studied them, followed their asses back and forth. Then we sprung the trap. How does a Recon platoon take on a company? Easy, man. By controlling the battlefield and preparing the killzone, tipping everything in our favor.

“We bottled them up in an open field surrounded by high ridgelines. There was a dirt road running through there with drainage ditches to either side. They sent out forward scouts and flanking guards and we took them out silently. When we had the main force where we wanted ‘em, well, we opened up, firing for effect. We dropped twenty of them in the first exchange from our hides on the ridge. The rest did exactly what we wanted them to, what any infantry grunt would: they all jumped into the ditches for cover. Bad decision. We had the ditches mined with explosives. When they jumped in, we tied them down with machine gun and small arms fire, a few grenades to keep them bunched. Then we blew the ditches and took out over a hundred men in like ten seconds. Perfect ambush. Absolute clockwork.”

“Sweet,” I said. “But we’re not dealing with soldiers. We’re not even dealing with living men.”

“Which makes it all that much easier,” Jimmy said.

“Right,” Tuck said. “See, these are deadheads. They only want one thing: meat. They have no sense of self-preservation or defense, no cunning, no nothing. They’re stupid. They come in numbers. They only want meat. We prepare an ambush site, we tip the odds in our favor. We throw some bait at ‘em to draw ‘em in and then we close the lid on those motherfuckers.”

I supposed it would work.

His plan was for the three of us and Diane to set up an ambush outside the fence. He had already selected the site. We would make it ready and then draw them in. Curtains.

“What’s the bait?” I said. “Not Diane.”

“Hell no!” Tuck said. “You think I got no sense of honor? No, not Diane. I got somebody better. Somebody big and juicy who can run fast. I got you.”

Shit. I should have seen that coming.

But I supposed it made sense. I was much younger than Tuck or Jimmy. I had combat experience. I was still pretty fast and I had yet to see my fortieth birthday and wouldn’t for another six years. Why not me? I was the logical candidate. So logical that I knew I could not tell Ricki about it or she’d have birds. She wouldn’t like the bait idea at all. In fact, she would get downright ugly about me risking my life. She would (as she had in the past) point out that I was a husband and a father and I had responsibilities. Which was true, of course, except that now the game had changed: I had responsibilities to not only Paul and her but to our little community at large.

That night, we did not mention what the game was.

Tuck took Diane off to the side and explained things to her and she was all for it, of course. We were all kind of excited about it. For so long now we’d been running from those damn things and now we were about to turn the hunters into the hunted and we liked the idea. There were over forty zombies out at the gate that night (Ricki counted). Their numbers were swelling fast. It was time for a decisive punch. Later, I wondered if Tuck was not so much interested in thinning the herds as he was in keeping our morale up. After three tours in ‘Nam he knew a thing or two about morale. I figured he understood a lot more about the practical side of human psychology than he let on.

We set up a charcoal grill out on the walkway and had ourselves a wienie roast that night. The kids were really excited about it all. Tuck was big on hot dogs. He watched his diet very carefully, subsisting on a lot of green vegetables and very lean cuts of meat. He drove us all nuts with his morning round of push-ups, sit-ups, pull-ups, and isometrics. He had but one decadent unhealthy indulgence and that was hot dogs. He had four huge walk-in freezers and the sheer amount of hot dogs in them was frightening. We didn’t have any hot dog buns and bakeries were pretty much cashed-in by that point, but being ever-resourceful Tuck made buns out of Indian flatbread that he then deep-fried. They were unbelievably good. We had a nice evening and Tuck even played a few songs for us on his fiddle.

Looking around at us sitting out there in lawn chairs I was struck by the fact that we were like some extended family now. Tuck was barely awake in his chair. Maria was curled-up on his lap with her arms around his neck, fast asleep. Diane and Paul and Davis were inside playing the only board game Tuck owned: Monopoly. Ricki and I were listening to Jimmy’s tales of being a teenager in West Side Manhattan back in the 1950’s and stealing apples from pushcart vendors. It was very

nice. A very calm, easy sort of night. And that’s the way I want to remember us: that night, everyone healthy and safe and relaxed in each other’s company.

Things had been going too well for too long and I knew it was going to change. I could feel something gathering around us, call that bad luck or fate or a sense of impending doom. I don’t know. But I could feel it and I knew there was trouble coming.

As it turned out, I was absolutely right.

AMBUSH

I remember back in infantry school at Fort Benning, our BC, Battalion Commander, telling us that in combat it was important to respect your enemy. Even if they were poorly-trained, poorly-organized, poorly-armed, and poorly-motivated. Because in every combat encounter or firefight there is the ugly element of chance that tips the odds away from you. That’s when things happen. That’s when you lose the advantage. That’s when things go to hell and men die for no good reason. Just like they say in the NFL, “on any given Sunday…” Meaning, that even the most ragtag bunch of players can kick ass on the hottest team out there. It happens. Maybe that ragtag team in question has not won a game all year, but when you get arrogant and let your guard down you can be sure that they’ll stomp you.

Respect your enemy.

Of course, we were in a pretty unique position being that our adversaries were zombies.

The thing was, what we knew about them we could have fit in a thimble. They were basically driven by hunger. They needed to bite and chew, to feed. They seemed to have no other primary motivation. They were not intelligent that I had ever seen or cunning or fast. But they were still scary. And what made them even scarier was that they came in numbers, in crowds, in mobs. I didn’t believe there was any cohesion to those mobs, no organization: they were just mindless eating machines that grouped together because they all wanted to eat. Tuck said they had no true survival instinct or sense of self-preservation. I agreed. They would charge in to bite regardless of the firepower you displayed or how many of their zombie associates you put down.

Necrophobia - 01

Necrophobia - 01 The Squirming

The Squirming Necrophobia 4

Necrophobia 4 Necrophobia - 02

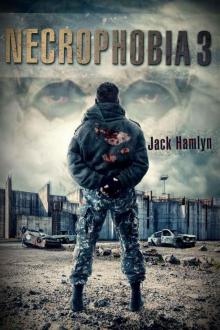

Necrophobia - 02 Necrophobia #3

Necrophobia #3