- Home

- Jack Hamlyn

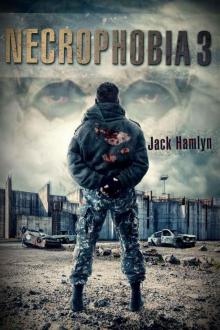

Necrophobia #3

Necrophobia #3 Read online

NECROPHOBIA

Book #3: Survival Games

By

Jack Hamlyn

SHOT DOWN IN FLAMES

The impact was like a shockwave.

The chopper careened into the trees like a swatted fly. There was no way Jonesy could get it under control in time to save our bacon. The RPG—because that’s what it had to be—slammed into the underside, making the Blackhawk jerk as if it had been kicked. Whatever the reason, it didn’t instantly detonate. If it had, we would have been blown to pieces. Instead, the rocket did the impossible: it skidded along the fuselage for maybe a second or two before going off.

The explosion was violent. Resounding.

That’s what I remember. The impact tossed the chopper and threw us in our harnesses. The whiplash felt like my head had been batted off my neck. The Blackhawk dove down into the darkness, nose-first, a gaping hole ripped into the rear of the cabin, the tail boom ripped free like the wing of an insect. Flames and smoke filled the cabin.

“WE’RE GOING DOWN!” Jonesy cried. “JESUS CHRIST, WE’RE GOING DOWN—”

What happened next, took bare seconds in real time. But in the spinning cabin, it seemed to go on and on. We hit the trees and the main rotor ripped into them like a buzzsaw, throwing a barrage of green brush at the cockpit bubble. We bounced, jerked, then hit the trees again. And in that frozen second of terror, I saw a rotor blade that had broken free spinning end over end at the bubble like a boomerang. It must have snapped free and been deflected by the trees right back at us.

There was no avoiding it.

And no way to get out of the harness in time.

By the time I saw it and my brain processed it—microseconds—it hit with full force, shearing through the cockpit bubble like the blade of a machete. Jonesy screamed right before it took his head off. I didn’t see much of that because of the smoke and the flames.

The chopper hit more trees, breaking apart, raining pieces of metal and plastic composite as it flipped end over end and burning fuel gushed into the cockpit. I barely had time to feel the heat before we hit with a jarring crash that knocked me senseless.

When I came to, probably seconds later, the cockpit was filling with dark, chill waters. I opened my eyes in time to see the blackness envelop me. I could feel the slow downward pull of the mangled chopper as it sank deeper and deeper into the murky waters.

I fumbled at my harness, trying to find the release.

I was strapped in tight. The chopper was sinking upside down and I couldn’t find the fucking latch. Then the harness finally released beneath my clawing fingers and I fought free of the straps. They were heavy and almost greasy in the waters like clutching tentacles.

Underwater…the chopper mangled…upside down…it was hard to orient myself. I fought for escape in the flooded cockpit, but every way I turned, I bashed into a wall, an obstruction. Once my fingers brushed the stump of Jonesy’s neck. My lungs aching, my limbs feeling thick and numb, I found an opening and scooted through, propelling myself into the black waters like a torpedo. I think the opening I found was the one the RPG opened up in the rear of the cabin.

I swam with everything I had, up, up, up, forcing my lungs not to suck in air and drown me. About the time I saw white dots popping before my eyes like bubbles, I surfaced, gasping and flailing my arms madly. I made enough racket to wake the dead of three counties…not a pleasant thought under the circumstances, the world trembling beneath the toxic eye of Necrophage. As oxygen filled my lungs, I calmed, and my brain started working.

I was treading water.

I did it instinctively.

I was in the center of a wide river whose waters gleamed in the moonlight, much of that from the oil slick left by the downed bird. Leafy branches and limbs floated by. I figured the chopper had cut them free and carried them into the river with us.

What now? I thought. You’re down in a river in the middle of the goddamn night, somewhere in the Catskills. Somebody out there wants you dead. Every time you think you’re getting a handle on things, they get a handle on you.

A good-sized tree limb floated by and I grabbed a hold of it. I floated and rested and did some thinking. I’d been through too much to call it quits now. I had to make it to shore. I had to survive the river.

Then the real surviving would begin.

THE QUEST

I was on a hunt.

I was searching for my son, Paul. Now that his mother was dead, an ugly and painful set of circumstances to say the least, he was all I had left. He was the only reason I got up in the morning and put one foot in front of the other. I prayed he was safe. He was with my friends and I knew he would be. They would die protecting him. Regardless, he needed me and I needed him. Through a series of unlucky, truly fucked up events, I had been separated from him. I ended up the prisoner of a wacko militia run by an ex-military psychopath and was forced to join in his war of extermination against the zombies that swarmed the streets of the Big Apple.

I made my escape when the living dead overran the militia encampment on the Lower East Side, hijacking the chopper and Jonesy, its pilot. Both of which were on the bottom of the river now. We’d searched Yonkers for my son and friends, seeking out the places I knew they might wait for me. At a public works garage my friends and I had used as a sort of temporary HQ, we found a note tacked to a corkboard. It read:

STEVE

UP TO THE KILLS

FOLLOW US

The ‘Kills, of course, were the Catskills in Southeastern New York state. That’s where my pal Tuck had taken everyone. I was sure of it. Up to the farm of a Vietnam vet (like Tuck himself) named Bobby Hughes who had a spread up near Doubletop Mountain. Many years before, after returning disillusioned from the war, Hughes had set up sort of a commune up in the ‘Kills with one goal in mind: to turn his back on the world, its petty hatreds, intolerances, and wars. His plan was to live a 19th century existence as a sustenance farmer and mountain man. To live off the land, care for it, and let it provide.

When Tuck and the others had pulled out for the ‘Kills, I was a prisoner of the militia. By that point, they had no idea whether I was alive or dead. That they had searched for me, I had no doubt. That it had pained them to leave me behind, I was certain. But in the end, they must have done the only reasonable thing: they headed for the mountains.

Paul was with them, of course.

I hoped he was safe.

I hoped they all were safe and had made it up to Bobby Hughes’ farm without incident. Although I knew they’d fight to death for my son and treat him as their own, I still worried. There was so much danger since the collapse of civilization. Militias. Cults. Psychotic survivalists. And zombies, of course. Ravening armies of them. Maybe even worse things.

So I worried.

And I would continue to do so until I saw him again. He was ten-years old. In many ways, with all he had seen in the dark months since The Awakening, he was more than a boy. He was a little man…yet, he was a boy. A boy that watched his mother die and was probably in a very fragile state, thinking that his old man was dead, too.

But I would get to him.

I would find him.

I would not let him down.

That was my promise to him and to myself. I planned on seriously hurting anyone that got in the way of that.

RIVER RATS

The current was slow and easy, but persistent.

It carried me downriver and out to the sea, for all I knew. I had been burned by the fuel fire in the cockpit; not badly, but enough so that my face felt hot and tender like a good July sunburn. If we hadn’t have crashed in the river, I would have been slow-roasted like an Oscar Meyer weenie. My burns were minor, considering.

Out of harm’s way for the time

being, I tried to put things together.

Somebody had fired that RPG.

Somebody who wanted us dead.

There was always the possibility that it was an accident. That it was fired by some lone survivalist or ragtag militia that thought we were out on some kind of raiding mission. I knew that in the City itself, and outlying areas like Yonkers and Mount Vernon, there were dozens of paramilitary armies and survivalist enclaves. Most were strictly small-timers, but ARM (the American Resistance Movement) was well-supplied, organized, and motivated. They had choppers and the crews to fly them. Maybe our RPG shooter thought we were with them. I didn’t think ARM was operating this far out in the boonies—I certainly hoped not—but that didn’t mean they were the only militia with helicopters, bad attitudes, and plenty of enemies. I was hoping I’d left those kind of assholes back in the City…but you just never knew.

After I drifted for a good fifteen or twenty minutes, I saw a dark mass in the distance. It took me a few seconds in the moonlight to realize it was a bridge. Bridges meant roads and I needed a road so I could find Doubletop Mountain and Bobby Hughes’ farm. By my calculations, taken just before the crash, I was good ten or fifteen miles away.

The bridge would be my debarkation point, I decided. I needed to get out of the water. I was getting numb.

It seemed like a good plan.

When I was maybe forty feet away, I saw lights. They exploded everywhere, spoking flashlight beams. They were scanning the river and it didn’t take long before they found me.

“There!” a voice shouted. “Right there on that log! There’s one of ‘em! That’s one of ‘em that killed your boy, Bill!”

Suddenly, all the lights were on me.

Shit.

About the time they started shooting at me, I dove deep like a beaver, losing myself in the dark, chill waters. I started swimming towards the far bank where the trees overhung the river. There were stands of reeds and snagged logs to hide amongst. I swam as far and fast as I could underwater. Finally, I had to come up. I broke the surface with barely a ripple like a frogman reconnoitering an enemy beach. I sucked in a few breaths. I figured I swam about twenty feet.

Bill and the boys were still at it, cracking off rounds like a bunch of yahoos on the first day of deer season. Lights were panning the waters and bullets were flying. Crack, crack, crack. I heard a few thud into the riverbank just down from me.

I ducked down again and swam underwater another twenty feet, then repeated the process until I ran into the reeds. The bottom was squishy and loose, so I pushed in closer to the bank, finding a mossy log and clinging to it.

I was in a hell of a state.

Nothing but the militia-issue fatigues on my back and the Gerber knife in my belt. My rifle went down with the chopper along with my pack. It was night and I had no idea where I was. To top it off, a bunch of armed crazies were shooting at me because they thought I had killed Bill’s son.

It couldn’t get much worse, I thought.

WILD BILL

Bill and the boys were not going to be denied me.

They started working their way along the banks, flashing their lights around, taking potshots at any suspicious objects. It was only a matter of time before they found me and either killed me outright or made a spectacle of my death. If I had anything to say about it, it was going to be neither.

I could hear them edging in closer.

The breeze brought me their odor which was home-brewed corn liquor strong enough to curl my nose hairs. There was no way I was going to talk my way out of this. They were drunk, armed, and intolerant. I was toast.

I had a choice to make.

Either I worked my way to the bank and slipped off through the woods or I took my chances in the reeds. The cover wasn’t bad where I was, but if they spotted me, it was a turkey shoot. On the other hand, if I made it out of the water, I was going to have to cover about twenty or thirty yards of open ground. And this in the moonlight.

I decided to wait it out.

When they got close, I ducked my face down in the water behind the log so it was half-way under. My nose just broke the surface, enough to suck in a few breaths. Bill and the boys started shining their lights in the reeds trying to find me. My head was behind the log, one hand gripping the knob of a long gone branch.

The lights found the log.

One of Bill’s boys opened up. A couple medium caliber slugs drilled into the log. One of them just inches from my hand.

“I think you got it, Tiny,” a voice said. “That log ain’t gonna hurt anyone anymore.”

A bunch of the boys started laughing. I smiled myself because Tiny’s instincts were much better than the rest of those yahoos. Tiny called them assholes and the whole lot of them moved off down the bank, making sport of Tiny, Champion Log Killer. I waited another ten minutes until their voices faded and the spears of their lights were down near the bend.

Then I made my move.

I pushed carefully through the reeds, edging closer to the bank until my fingers pressed into the grass. I tried to slide out of the water quietly and gracefully, but you know how it is when you’re waterlogged—you weigh 300 pounds and your clothes feel like they’re crusted with cement. It didn’t help that the water was cool and my limbs were numb. So, I didn’t pull myself up as soundlessly as I’d hoped; I splashed and fought my way up like a drowning water buffalo. If no one heard, then they were stone deaf. I pulled myself through the grass and got to my knees. Slowly, very slowly, I stood up.

That’s when I saw I wasn’t alone.

Someone was standing there.

A very big someone.

“Who—” I started to say, but they reached out and took hold of me. I was too waterlogged to move fast and avoid the hands that grabbed me. I was seized and yanked right off my feet and into the air like I was stuffed with feathers. Right away, I smelled something nauseating like rotten pork on a steam tray.

A zombie.

He, or it, pulled me up into the air so I was at face level for easy gnawing. I felt like a chicken wing plucked off a plate.

The zombie made a growling, guttural noise and I saw his teeth gleaming in the pale moonlight. Suddenly, I didn’t feel so waterlogged or slow. As he pulled me towards his waiting mouth, I moved quickly with sheer instinct. There was no time to get at my knife. I jabbed my thumbs into the deadhead’s eye sockets with everything I had and felt his eyes squish like rotten grapes. They splashed over my fingers in a warm gush of pulp.

The zombie made a hoarse grunting sound which must have been his decayed brain’s idea of pain.

He tossed me and I rolled into the underbrush.

I struggled to my feet and broke into a panicked run across the open, moonlit ground. I had just made the shadowy tangle of the woods when I heard men running and voices crying out. Flashlight beams were cutting through the dark, bobbing as the men who held them ran.

“There! Right there!” one of them shouted. “He’s right goddamn there!”

I hit the ground, covering my head and making a low profile of myself. They weren’t interested in me. They had their lights concentrated on the hulking, undead figure stumbling in the moonlight.

“That’s the one!” Tiny shouted. “That’s the one that killed your boy, Bill!”

I watched from cover as they opened up with a fury on the now-blind Frankenstein-ish figure. One good round through the head would have done the trick, but what fun was that when you were drunk, armed, and your cold little heart was set on some serious overkill? They hit the deadhead with thirty or forty rounds, drilling slugs through him and blasting him apart. I think he was dead—or no longer animate, if you prefer—seconds into it. But they kept shooting, laying down such a heavy volume of fire that he simply couldn’t drop. Mr. Zombie danced like a marionette, spinning in clumsy half-circles, pieces of his anatomy flying free until there wasn’t enough left to stand.

The corpse went down in a mutilated heap.

His remains

were easily spread thirty feet. Bill and the boys stood around their kill like they had dropped a deadly and cunning man-eating leopard instead of an eyeless, decomposing cannibal corpse. I suppose to them, it was the same thing. They kept their lights on it in case it tried anything funny.

“Well, he’s dead all right,” Tiny said.

“You sure?” one of them said.

“I bet some mouth-to-mouth can get him walking again,” said another.

They all started laughing.

“Kiss my ass,” Tiny told them.

More laughter. They passed the bottle and the smell of it was like cheap floor polish. I was thirsty, but not that thirsty. After more ribbing and good humor, Bill—I assumed it was Bill—told them to put the bottle away, there was work to be done.

“We’re just blowing off some steam,” one of them said.

Things got real quiet then. I could hear the crickets.

“That ain’t the one that got Georgie. That ain’t the one at all,” Bill said. From the tone of his voice, I got the feeling that old Bill wasn’t strictly right in the head. The others got real quiet when he spoke like they were afraid of him.

“Let’s get back on the road. That other one must be still around here. I want him.”

“Ah, let’s call it a night, Bill. They’re easier to hunt in the daylight,” Tiny said.

“Hell you say?”

“Well, Bill, I just mean that—”

“Yeah, I know what you mean, you gutless smear of shit,” Bill said, as he pushed his way through the others, bearing down on Tiny. They fell right out of his way. “That’s all my boy means to you, is it? That’s all poor Georgie was to you. Just a turd that got stepped on and you’re more than happy to wipe his memory off like shit on a shoe.”

“He didn’t mean anything, Bill,” one of them said.

Bill got about three inches from his face. “You shut the fuck up and get out of my way before I break my fists on your head.”

Necrophobia - 01

Necrophobia - 01 The Squirming

The Squirming Necrophobia 4

Necrophobia 4 Necrophobia - 02

Necrophobia - 02 Necrophobia #3

Necrophobia #3