- Home

- Jack Hamlyn

Necrophobia - 02 Page 24

Necrophobia - 02 Read online

Page 24

“Damn zombies,” he repeated. Basky mentally chuckled to himself. He couldn’t believe he had actually said ‘zombie’, but what else do you call the walking dead, and God knows that was what everyone had become. When the supply plane from Mawson base had arrived at Casey thirty-six hours earlier, both pilots had professed to suffering from a simple case of the flu, which seemed to be running rampant in Mawson, as well as most of Australia and New Zealand. Doc Wiggins had forced both of them to don surgical masks for the duration of their turnaround. It was an ordinary precaution. Flu in a closed environment like an Antarctic base was a real health concern. The pilot and co-pilot’s deaths less than twelve hours later came as a shock to everyone, especially Wiggins. When they both revived a few hours later and began attacking people, biting, clawing, and God help them all, eating human flesh and drinking blood, it had rapidly become a bad horror movie with every man for himself.

“Craig. How are you holding out?” he asked quietly, as his companion shivered violently.

“C-c-cold,” Dylan moaned, his teeth chattering. “I need more heat.”

“Okay.” Basky broke up another chair as quietly as he could and added it to the small pile of embers in the fire. The tiny fire added little heat to the room, but its psychological effect was immense. The soft glow reminded him that he was civilized and not simply meat in a freezer waiting to be eaten. He held his breath when the flames flickered violently and smoke billowed. The wind was picking up, forcing most of the smoke back inside. Now, he could add the threat of suffocation to their ever-growing list of immediate problems.

“Rog,” Dylan said a few minutes later. “I feel so sick, like my insides are twisting around. My forehead is wet with sweat, but I’m freezing. Am I dying, like the others?”

Basky shook his head, though he knew Dylan could not see the gesture. “No, Craig. You’re just sick, that’s all. Your arm is infected.”

“If I die and turn into . . . one of them, you’ll do me, right?”

“You won’t.”

Dylan’s weak voice took on an edge of desperation. “Promise,” he pleaded.

Basky sighed. His breath formed a cloud between him and Dylan, thankfully hiding Dylan’s frightened face from him. “Okay, Craig, I promise. Now, get some sleep.”

Less than an hour later, Dylan gasped out a last pitiful breath and his body began to shudder. Then he lay still. Basky checked his friend’s pulse with numb fingers to make sure he was dead, but could feel nothing. He stared at Dylan for several minutes, but saw no movement. Dylan was dead.

“Sorry, Craig,” he said. Basky took a splintered chair leg and drove the sharp point into Dylan’s chest. Fearing this wasn’t enough; he took a metal letter opener from the desk and began to hack Dylan’s head from his body. It was a crude and messy job and made him sick to his stomach, but he had seen too many mangled corpses return to life. He wasn’t going to take any chances. Besides, he had promised Dylan.

The power had been off for hours and the base buildings were cooling down rapidly. Basky estimated that, by now, it must be ten or fifteen degrees below in the rest of the unheated buildings, and even colder outside. At some point, if he survived long enough, he hoped even zombies would freeze. Then, he would make his escape, though he wasn’t sure where he could run. He couldn’t fly either of the planes parked on the frozen runway, and the nearest shelter was the American base at McMurdo several days away by tractor, probably more than that with a storm approaching.

All he could do was keep the fire going and hope the door held.

3

Aug. 26, 2013 Somewhere on the Antarctic Ice Shield, Antarctica

A vast, milky-white emptiness, bordered only by a thin line of blue sky, a frozen land devoid of life, and as barren and as dry as the plains of Mars, central Antarctica seemed especially designed to reduce the stature of any human foolhardy enough to dare defy its boundaries to one of wretched insignificance.

The chilling minus 65-degree C. temperature seeped into Val Marino’s bones like water in a sponge. A fleece balaclava hood covered his head and mouth and it prevented him from inhaling the cold dry air directly into his lungs, but it did not cover his moustache, which was an icicle dangling beneath his nose. His breath, exhaled through his balaclava, formed a cloud in front of his face before the moisture crystallized and fell at his feet. When he clapped his mittens hands together and stamped his feet on the frozen snow to get the blood circulating, it felt as if tiny needles pricking his extremities. It was time to get moving. He turned to Elliot Anson working beside him.

“Do you have that ice core sample yet, Elliot? My balls are freezing off. Let’s get out of here.”

Anson chuckled. “I thought you wanted to see the wonders of Antarctica?”

“That was two weeks ago. Now I’m just freezing my balls off and wishing I was back in Arizona.”

As the only American on the research team, Marino had taken a lot of kidding from the gruff Australians at Casey base, but he and Anson got along well enough. Anson, from Melbourne, was one of the few of whom he could understand every word except when Anson deliberately slipped into ‘stine’, an outback Australian dialect, to aggravate him. When the Aussie climatologist had asked him to accompany him out onto the ice, Marino had jumped at the chance to escape the confines of the base. Now, he was beginning to regret his decision.

Anson pulled the meter and a half long meter corer out of the ice, removed the five-centimeter diameter ice core from its hollow center, and placed the sample in a box on the rear of the Sno-Cat. Then he opened the door, tossed the metal corer in the back, and struggled to crawl inside. He was a bit ungainly, garbed as he was in four layers of insulated clothing. Once situated, he removed his outer mittens so he could drive the tractor. His inner mittens were a bright orange, matching his parka and wind suit.

Marino climbed in the passenger side seat beside him, but kept his mittens on. He wore all red. In the Antarctic, bright colors were useful safety features and not merely fashion statements. They also served as means of identification when multiple layers of bulky clothing masked faces and all other identifying features. He did not particularly like red, thinking it a somewhat non-masculine color, but would have worn chartreuse if it were visible from several kilometers away and warm.

“Does this thing have a heater?” he asked with a touch of sarcasm. Anson, more used to the Antarctic temperatures than Marino, tended to drive with the heater off, complaining his breath frosted the windscreen. At forty-six, Anson was a veteran to the frozen southern continent, having spent nearly fifteen seasons at one Australian base or another.

Anson cranked the Sno-Cat’s diesel engine. “Sure, it will be up to twenty below in no time at all,” he said with a grin.

Anson and Marino were twenty kilometers from their winter camp of two weeks, taking shallow ice core samples, monitoring air temperatures, and taking instrument readings at numerous remote air-sampling stations in an effort to calculate the desertification of central Australia. For decades, the deserts had been encroaching on once fertile land as rain patterns shifted northward to Borneo. Periodically, colossal dust storms had swept out of the Outback to inundate eastern Australia, including Melbourne and Sydney, in fine red dust, Australia’s new version of a winter blizzard. Anson’s team was determined to conclude just how serious the problem was.

As the Sno-Cat sped across eons-old hard packed snow, headlights casting twin pools of light into the gloomy Antarctic darkness, Marino slowly chipped away the ice from his frozen moustache.

Anson glanced at him. “One day, you’re going to break that bloody thing off.”

“When we get back to base, I’m shaving it off. I’m tired of having a snotcicle hanging from my nose every time we go out.”

Anson guffawed, “I can see where that might be a problem. It’s what we call a bush oyster.”

“Very descriptive. I thought it would keep my nose warm.”

“It’s too small for that, mate.”

Marino winced at Anson’s veiled reference to his prominent Roman nose. On his gaunt six-foot frame, Marino thought his nose looked dignified, even patrician. “I’m proud of my nose. I have the blood of Caesars running through my veins.”

“Yeah, mate, but it’s too bloody thin to keep you warm.”

As the temperature of the cab of the Sno-Cat slowly rose, Marino began to shed layers of clothing. First, he removed his outer mittens so he could manipulate the zipper on his windbreaker and pull his balaclava over his head, revealing his long, curly black hair. Everything else, he left on for the short trip back to camp. He grabbed his white Stetson, his reminder of Arizona and placed it on his head. The silver and turquoise hatband had been a going away present from his girlfriend. The Red-Tailed Hawk feather protruding from it, he had found lying on his doorstep as he left his apartment, a lucky find. He brusquely rubbed his hands to warm them. As he looked out at the bleak, frozen landscape, he realized just how much he missed winters in Tucson when he could usually wear shorts, a t-shirt, and sandals during the day and a light jacket or sweater at night. In Antarctica, you wore two layers of clothing to the bathroom.

Of course, with the seasons south of the equator reversed, it was late summer in Arizona and about 100 degrees Fahrenheit, or 37.7 Celsius as everyone else measured it. The summer monsoons would almost be over. It would be cool enough at night to sit on the veranda and dine under the stars. Marino sighed, homesick. His visible breath brought him back abruptly to the reality of where he was.

The top of the red tent that had served as their home away from home for the past two weeks rose slowly and deceptively above the horizon, barely visible in the gloom of the Antarctic night. It appeared to be only a short hike away, but Marino knew it was at least another five kilometers. Distances could be deceiving in a land with no fixed points of reference. It was easy to get lost in the vast emptiness of the Eastern Antarctic Ice Sheet.

“One more night and we pack it in and head back, right? I’ll be glad for a hot cooked meal. I’m tired of canned food and ration bars.”

Anson smiled, “Night? Do you mean a regular night or the one hundred and thirty days Antarctic night?”

“Twenty-four hours, then. You know what I mean.”

“Yeah. Sorry. Stale joke. What’s your hurry? You have everything you need all packed into a nutritious chewy bar. What more could you want, Vegemite?”

Marino made a face at Anson. Vegemite, made from a yeast extract, was an Australian staple, spread on toast, bread, and almost everything else at Casey Base.

“Yuck! I don’t want Vegemite, Marmite, Promite, or any other food that ends in ‘mite’. I want Yankee Pot Roast with red potatoes and gravy, or maybe sliced turkey with cranberry sauce. With oyster stuffing,” he added after a moment’s consideration.

Anson laughed, “Right. Right. One more night and we leave, and for your irreverence concerning our national cuisine, tonight you cook.”

The crackle of the radio interrupted Marino’s retort. He recognized the language as Russian, which he did not speak. The voice sounded frantic.

“Can you understand him?”

Listening, Anson cocked his head to one side and then motioned for silence. After following the disjointed conversation for several minutes, made even more difficult by the signal fading in and out, his face turned ashen.

“What is it?” Marino asked with growing concern. His big Australian partner had proven unflappable since they had first met. Now, he seemed to be in a trance. Anything that bothered Anson, chilled Marino right through his thermal underwear.

The signal faded and vanished. Anson shook his head, slowly coming out of his daze.

“What?” Marino repeated.

Anson’s eyes were cold, his voice somber. “I couldn’t follow all of it. He spoke with a very deep accent from somewhere in the Urals. Something bad has happened at Vostok.”

Marino knew the Russian base was at Lake Vostok, some 1300 kilometers from the Geographic South Pole, about 500 kilometers from their camp. “Did he say what?”

“My Russian is limited to jokes and bar talk, but it sounded like people were dying at Vostok. He mentioned a fire.”

“Damn.” Marino knew that in Antarctica, fire was second in danger, only to freezing to death. By the look on Anson’s face, Marino suspected his friend was not telling him everything. “What else?”

“Well, I missed most of it, but he said something about Casey. He said they had gone first.”

“Gone first? What does that mean?”

Anson shook his head. “I don’t know. It sounded like he was radioing one of their research teams out on the ice. They didn’t respond.”

“What do we do?”

Anson rubbed his chin with a gloved hand. “By the time we reach Casey, we won’t be much help.”

“What about Vostok?” Marino asked.

“It’s out of the way. If we leave, we should head directly for Casey.”

Anson brought the Sno-Cat to a lurching halt right at the door of their tent. Marino, caught up in his thoughts, had not noticed that they had arrived. He leaped out of the cab and rushed inside, grabbing food, water, clothing, extra fuel, and both rifles. He took a quick look around – a jumble of wooden crates, two folding cots, a small stove, and a folding table full of scientific equipment. They could leave the tent and most of the supplies. Dragging the sled behind the Sno-Cat would only slow them down. Reluctantly, he decided to leave his favorite books by Hawthorne and Thoreau, but he quickly scooped up his iPod, and shoved it in an outer pocket.

Anson walked into the tent, allowing a blast of frigid air to enter with him. He stopped a moment to watch Marino frantically hurrying around the tent packing and sat down on his cot. “If you’re so damn energetic, cook some food for us.”

Marino stopped and stared at his companion. “How can you eat? We have to get to Casey.”

“I’m hungry,” he said as he lit the heater. “You need a hot meal, too. All we’ll have on the journey is cold protein bars and warm chocolate. We both need the energy. Our bodies’ burn 4-6,000 calories a day in this cold climate; remember. We need the calories for body heat. Make some pasta. The carbs will fight off fatigue syndrome, and we need sleep. I’m tired. Sleep first and then we leave.”

Marino remembered the long lectures on proper nutrition that he had sat through when he had arrived at Casey. A diet too high in fat and too low in carbohydrates could result in dizziness or violent mood swings, symptoms of fatigue syndrome.

In defeat, he dropped his pack. He was eager to leave, but he knew Anson was right. “Yeah, yeah, I’ll cook us some penne with marinara and frozen vegetables. After all, I am Italian.”

After their meal and cups of hot chocolate, which they drank more for the extra calories, than out of preference, Marino cleaned up the dirty dishes by rubbing them with snow. Wistfully, he glanced at their empty container of coffee. While, Anson preferred tea to coffee, Marino missed his daily jolt of caffeine. He had run out two days earlier than he had planned. Anson dropped off to sleep quickly, but Marino slept fitfully as dark images of what they might find played in his mind.

* * * *

The next day, the journey passed mostly in silence, each man embroiled in his private war against dark, foreboding thoughts. Nothing more came through on the radio. Moreover, they could not reach Vostok or any other base. The radio airwaves were dead, an ominous sign.

“Maybe it was a solar flare,” Marino suggested, after a lengthy silence, bored with watching the tedious lack of scenery pass by. “The aurora australis has been spectacularly active the past week. That would mess up the ionosphere, right?”

Anson pursed his lips, “Perhaps, but that wouldn’t explain the dire message. No, I am afraid that something bad has happened.”

“Like what?”

Anson shrugged, “I can’t say.”

Marino could not shake the worried feeling that Anson was withholding something, but he did no

t want to press him on it. The taciturn Aussie was often miserly with information, dealing it out like currency in a land where money has no value. Information and close-knit relationships with fellow residents of Antarctica could save your life and make living in a frozen hell more bearable. Marino realized he had neither. He was a visitor, an American to boot, not fully trusted, and certainly misunderstood. Everyone was jovial enough around him, but he often had trouble following their conversations. He felt like a third wheel on a bicycle. He looked at Anson. Even now, the big Australian’s face was a blank mask. Devoid of emotion or a clue to his inner thoughts, it could have been chiseled from ice.

After a few hours, Marino grew weary of just sitting, so he decided to volunteer to drive while they were still out on the relative flatness of the ice plains. Later, as they neared the coast of Antarctica, things would get hairy. Since Anson was the better driver of the two, Marino figured it would be safer for Anson to drive over the more precarious terrain.

“Let me take over for a while.”

Anson glanced at him and nodded. Switching positions was not easy in the confines of the small cabin, but opening the doors and allowing what little warmth the cabin contained to escape, was not an option. Anson settled back in his seat and closed his eyes. They drove in silence with the sound of the Sno-Cat’s engine almost lulling Marino to sleep. He debated trying the radio once more, but knew it was no use. He glanced over at Anson sleeping soundly in the passenger seat and wondered how he could sleep at all. A vague tightness in the pit of Marino’s stomach gnawed at his insides. Anson seemed to shrug off such worries. He wondered how anyone could be so cold. Then, he realized Anson was simply resting up for the ordeal, whatever it was, that lay ahead of them.

Necrophobia - 01

Necrophobia - 01 The Squirming

The Squirming Necrophobia 4

Necrophobia 4 Necrophobia - 02

Necrophobia - 02 Necrophobia #3

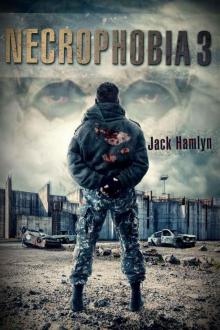

Necrophobia #3